Django Time

Wednesday, 02 September 2009

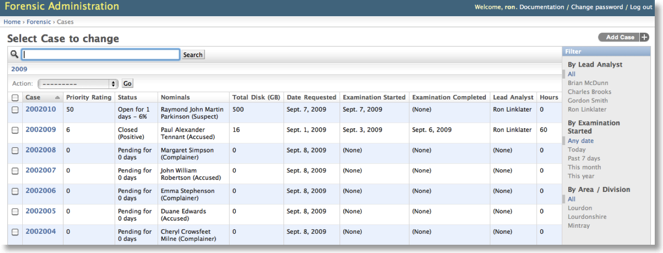

I was back home in Scotland in June and my dad happened to mention a problem he was having at work: he does forensic computer analysis and had written a case tracking system for his department in Access. However, the data model wasn’t normalized and he was finding it difficult to extend it to meet their growing needs. I’m not familiar with Access but I poked around a bit and did some googling, and it seemed like we could get it to at least support a couple of his desired changes, but it wasn’t going to be pretty.

It got me to thinking though, and when I got back to the States, I decided to try out re-implementing the system using Django. Django is a web framework for Python, and I had been meaning to find time to try it out for a while. You define your data models as Python objects and Django handles the ORM to get your data in and out of a database. It also provides APIs to query and manipulate the data easily from Python, and templating to help you display data in web pages.

I won’t presume that I could describe Django better than its authors, however, so here’s its features lifted straight from djangoproject.com:

Object-relational mapper

Define your data models entirely in Python. You get a rich, dynamic database-access API for free — but you can still write SQL if needed.

Automatic admin interface

Save yourself the tedious work of creating interfaces for people to add and update content. Django does that automatically, and it's production-ready.

Elegant URL design

Design pretty, cruft-free URLs with no framework-specific limitations. Be as flexible as you like.

Template system

Use Django's powerful, extensible and designer-friendly template language to separate design, content and Python code.

Cache system

Hook into memcached or other cache frameworks for super performance — caching is as granular as you need.

Internationalization

Django has full support for multi-language applications, letting you specify translation strings and providing hooks for language-specific functionality.

What particularly attracted me to Django is its amazing out-of-the-box administration interface. Django was developed in a news room environment, so they put together a pretty full-featured administration interface that lets journalists enter news articles, mark them for display on the newspaper’s public pages, and so on. The public-facing part of the site then uses Django’s template system in conjunction with is MVC framework to retrieve and present the data entered via the admin interface.

In my use case, the system would only be used by a small number of people, all of whom would have at least some form of administrative access. So, I figured I could get a pretty usable system without having to do any ‘webby’ stuff at all. And that’s been pretty much my experience: the bulk of the system is in two Python source files: one that defines the data model; and one that customizes the administration interface.

Django works with multiple databases, including SQLite, for which I have a definite soft spot. It also comes with a for-development web server built-in. Given the small number of users, I hoped that I could use SQLite and the built-in web server for the final version, thereby saving my dad from having to install and maintain database and web servers. The built-in server isn’t meant to be used in production, but we’ll see how it does. The system doesn’t have enough run time on it yet, but if it proves unreliable then switching to a full web server won’t be too painful. I don’t foresee SQLite being a bottleneck, but if it does we can switch it to MySQL or Postgres or something, although I’d need to convert the data to do that probably.

The Django site has an excellent four-part tutorial that walks you through most of its aspects. It was certainly enough to get me going. The online documentation for the APIs is also very good. It didn’t take long at all to get a proof-of-concept up and running for my dad to try out. We used basecamp to keep track of things as we worked through the nitty gritty of the design, git to track the source, and a couple of Django sites at my web host so my dad could play with the system as it came together (kudos to Andrew at dreamhost for helping me get Passenger WSGI going with Django by the way).

In just a few weeks of working on it spare time the system is up and running, complete with a couple of reports (HTML and CSV) and some features not envisaged at the outset (ain’t that always the way?). I even wrote an importer that took the old cases from Access via a CSV file and imported them into the new one, using Django’s model classes so that I didn’t even have to write a single INSERT statement.

If you're a pythony sort of person then I highly recommend taking a look at Django for your next webby projecty thingy.

It got me to thinking though, and when I got back to the States, I decided to try out re-implementing the system using Django. Django is a web framework for Python, and I had been meaning to find time to try it out for a while. You define your data models as Python objects and Django handles the ORM to get your data in and out of a database. It also provides APIs to query and manipulate the data easily from Python, and templating to help you display data in web pages.

I won’t presume that I could describe Django better than its authors, however, so here’s its features lifted straight from djangoproject.com:

Object-relational mapper

Define your data models entirely in Python. You get a rich, dynamic database-access API for free — but you can still write SQL if needed.

Automatic admin interface

Save yourself the tedious work of creating interfaces for people to add and update content. Django does that automatically, and it's production-ready.

Elegant URL design

Design pretty, cruft-free URLs with no framework-specific limitations. Be as flexible as you like.

Template system

Use Django's powerful, extensible and designer-friendly template language to separate design, content and Python code.

Cache system

Hook into memcached or other cache frameworks for super performance — caching is as granular as you need.

Internationalization

Django has full support for multi-language applications, letting you specify translation strings and providing hooks for language-specific functionality.

What particularly attracted me to Django is its amazing out-of-the-box administration interface. Django was developed in a news room environment, so they put together a pretty full-featured administration interface that lets journalists enter news articles, mark them for display on the newspaper’s public pages, and so on. The public-facing part of the site then uses Django’s template system in conjunction with is MVC framework to retrieve and present the data entered via the admin interface.

In my use case, the system would only be used by a small number of people, all of whom would have at least some form of administrative access. So, I figured I could get a pretty usable system without having to do any ‘webby’ stuff at all. And that’s been pretty much my experience: the bulk of the system is in two Python source files: one that defines the data model; and one that customizes the administration interface.

Django works with multiple databases, including SQLite, for which I have a definite soft spot. It also comes with a for-development web server built-in. Given the small number of users, I hoped that I could use SQLite and the built-in web server for the final version, thereby saving my dad from having to install and maintain database and web servers. The built-in server isn’t meant to be used in production, but we’ll see how it does. The system doesn’t have enough run time on it yet, but if it proves unreliable then switching to a full web server won’t be too painful. I don’t foresee SQLite being a bottleneck, but if it does we can switch it to MySQL or Postgres or something, although I’d need to convert the data to do that probably.

The Django site has an excellent four-part tutorial that walks you through most of its aspects. It was certainly enough to get me going. The online documentation for the APIs is also very good. It didn’t take long at all to get a proof-of-concept up and running for my dad to try out. We used basecamp to keep track of things as we worked through the nitty gritty of the design, git to track the source, and a couple of Django sites at my web host so my dad could play with the system as it came together (kudos to Andrew at dreamhost for helping me get Passenger WSGI going with Django by the way).

In just a few weeks of working on it spare time the system is up and running, complete with a couple of reports (HTML and CSV) and some features not envisaged at the outset (ain’t that always the way?). I even wrote an importer that took the old cases from Access via a CSV file and imported them into the new one, using Django’s model classes so that I didn’t even have to write a single INSERT statement.

If you're a pythony sort of person then I highly recommend taking a look at Django for your next webby projecty thingy.

Correct dates on Flickr photos

Friday, 17 August 2007

When I drank the Flickr cool-aid, I had to move all of my pictures from my home-grown Perl/CGI webserver setup. They uploaded to Flickr just fine, but quite a few of them had incorrect dates due to incorrect or missing EXIF information. Fortunately I had all of the image files named in the

Starting from the python script I had previously written to archive my photo tagging information (see this post), I just had to add a function that used a regular expression to parse the date information out of the photos' filenames and call

YYMMDD_n.JPG format, so I knew there had to be a way to fix their dates programmatically.Starting from the python script I had previously written to archive my photo tagging information (see this post), I just had to add a function that used a regular expression to parse the date information out of the photos' filenames and call

photos.set_Data in the Flickr API. The function is up on TextMate's pastie site for those interested.Backing up your Flickr photo info

Sunday, 12 August 2007

I gave up on my Perl/CGI scripted website for my kids' photos a couple of years back and moved them lock, stock and barrel to Flickr. It's a great service and I'm very happy with it. My initial upload was more than a thousand pictures, but I wanted to start out the right way so I tagged them all with people's names and so on. As you can imagine, this was pretty tedious, so I decided I would try and make sure I would never have to do that again. I did some digging around and came across the Flickr API. The authentication mechanism is a trifle cumbersome but some kind soul had already gone through the pain and posted a CC-licensed Python script that did most of the work. I messed around for a little bit and ended up with a little Python script that downloads an XML file for each photo in my photostream. The XML file contains all the metadata for the photo, including its title, description, tags, dates taken and posted. I run this script every week or so and it grabs the data for the pictures I've posted since the last time I ran it. This way I have all my photos' metadata in a parse-able form, so if Flickr should ever go away I can write something to parse the files and import them to whomever at that time.

I posted the script via TextMate's excellent Pastie service, in case anyone is interested. I had to strip out my Flickr API key and its shared secret (which you need in order to access the Flickr API) for obvious reasons, but it's simple enough to get your own from Flickr.

UPDATE April 3rd, 2008:

I had to update the script to pass the authorization token when looking up your username as it started returning "failed to find user". The updated script is linked above.

I posted the script via TextMate's excellent Pastie service, in case anyone is interested. I had to strip out my Flickr API key and its shared secret (which you need in order to access the Flickr API) for obvious reasons, but it's simple enough to get your own from Flickr.

UPDATE April 3rd, 2008:

I had to update the script to pass the authorization token when looking up your username as it started returning "failed to find user". The updated script is linked above.